|

Size: 54350

Comment:

|

Size: 59123

Comment:

|

| Deletions are marked like this. | Additions are marked like this. |

| Line 1: | Line 1: |

| == Tutorial 28: Connectivity == | = Tutorial 28: Connectivity = |

| Line 4: | Line 4: |

| ''Authors: Hossein Shahabi, Mansoureh Fahimi, Francois Tadel, Esther Florin, Sergul Aydore, Syed Ashrafulla, Takfarinas Medani''', '''Elizabeth Bock, Sylvain Baillet'' | ''Authors: Hossein Shahabi, Mansoureh Fahimi, Francois Tadel, Esther Florin, Sergul Aydore, Syed Ashrafulla, Takfarinas Medani, Elizabeth Bock, Sylvain Baillet'' Cognitive and perceptual functions are the result of coordinated activity of the functionally specialized neural modules distributed in the brain. [[http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Brain_connectivity|Brain connectivity]] investigates how these neural modules (or nodes) interact as a network, with the goal of having a better understanding of how the brain processes information under certain functions. Depending on which connectivity characteristic is studied, a distinction is made between '''structural''' (fiber pathways), '''functional''' (non-directed statistical dependency) and '''effective''' (causal interaction) connectivity between regions. Effective connectivity is often referred as directed functional connnectivity. In these tutorial we will see how to perform functional an effective connectivity analyses in Brainstorm, firstly with simulated data and later with real data. |

| Line 8: | Line 10: |

| == Introduction == During the past few years, the research focus in brain imaging moved from localizing functional regions to understanding how different regions interact together. It is now widely accepted that some of the brain functions are not supported by isolated regions but rather by a dense network of nodes interacting in various ways. Brain networks (connectivity) is a recently developed field of neuroscience which investigates interactions among regions of this vital organ. These networks can be identified using a wide range of connectivity measures applied on neurophysiological signals, either in time or frequency domain. The knowledge provides a comprehensive view of brain functions and mechanisms. This module of Brainstorm tries to facilitate the computation of brain networks and the representation of their corresponding graphs. Figure 1 illustrates a general framework to analyze brain networks. Preprocessing and source localization tasks for neural data are thoroughly described in previous sections of this tutorial. The connectivity module is designed to carry out remained steps, including the computation of connectivity measures, and statistical analysis and visualizations of networks. {{attachment:GeneralFlowConn.png||height="230",width="700"}} == General terms/considerations for a connectivity analysis == '''Sensors vs sources: '''The connectivity analysis can be performed either on sensor data (like EEG, MEG signals) or on reconstructed sources (voxels/scouts). '''Nature of the signals: ''' The selection of connectivity method depends on the nature of the data. Some approaches are more suitable for spontaneous data (resting state) while others work better with task data (trials). '''Point-based connectivity vs. full network: '''Most of the connectivity functions in this toolbox have the option to either compute the connectivity between one point (channel) and the rest of the network (1 x N) or the entire network (N x N). While the later calculates the graph thoroughly, the first option enjoys a faster computation and it is more useful when you are interested in the connectivity of an ROI with the other regions of the brain. '''Temporal resolution: '''Connectivity networks can be computed in two ways; static and dynamic. Time-varying networks can present the dynamics of brain networks. In contrast, the static graphs illustrate a general perspective of brain connectivity which is helpful in specific conditions. Users need to decide which type of network is more informative for their study. '''Time-frequency transformation: ''' Many connectivity measures use a time-frequency transformation to transfer the data to the frequency domain. These approaches include short time Fourier transform, Hilbert transform, and Morlet wavelet. '''Output data structure:''' Consequently, computed connectivity matrices in this toolbox have up to four dimensions; channels x channels x frequency bands x time. Also, when dealing with trials and several files, each file has that 4-D structure. |

== General considerations in connectivity analysis == '''Sensors or sources:''' Connectivity analysis can be performed on sensor data (EEG/MEG signals) or on reconstructed sources (voxels or scouts). '''Recording condition:''' While connectivity analysis can be performed on resting-state (spontaneous) and event-related (trials) recordings, the appropriate connectivity method depends on the recording condition. '''Point-based connectivity vs. full network:''' Connectivity can be computed between one node (aka seed) and the rest of the nodes in the network (1 x N approach), or between all the possible node pairs in the network (N x N approach). While the later calculates the detailed connectivity graph, the 1 x N approach is faster to compute and it is more useful when you are interested in the connectivity of a ROI with the other regions of the brain. '''Temporal resolution:''' Connectivity networks can be computed in two ways; static and dynamic. Time-varying networks can present the dynamics of brain networks. In contrast, the static graphs illustrate a general perspective of brain connectivity which is helpful in specific conditions. Users need to decide which type of network is more informative for their study. '''Time-frequency transformation: ''' Many connectivity methods rely on the [[Tutorials/TimeFrequency|time-frequency representation]] of the data. These approaches include short time Fourier transform, Hilbert transform, and Morlet wavelet. # {{attachment:GeneralFlowConn.png||width="700",height="230"}} |

| Line 31: | Line 24: |

| In order to compare different connectivity measures, we use simulated data with known ground truth. Consider three channels constructed using the following AR process. | In order to compare different connectivity measures, we use simulated data with known ground truth. Consider three channels constructed using the following autoregressive (AR) process. |

| Line 44: | Line 37: |

| {{attachment:SimSignals1.PNG||height="400",width="550"}} | {{attachment:SimSignals1.PNG||width="550",height="400"}} |

| Line 57: | Line 50: |

| {{attachment:TransferMatrix3_AR3.png||height="400",width="550"}} In this figure, the diagonal elements show the auto transfer function, which in our specific case the spectrum of the signals. The off-diagonal terms represent the interactions between different signals. Here, we see the transfer function from channel 1 to channel 3. |

{{attachment:TransferMatrix3_AR3.png||width="550",height="400"}} In this figure, the diagonal elements show the auto transfer function, which in our specific case is the spectrum of the signals. The off-diagonal terms represent the interactions between different signals. Here, we see the transfer function from channel 1 to channel 3. |

| Line 63: | Line 56: |

| {{attachment:Directed transfer function_AR3.png|Directed transfer function_AR3.png|height="400",width="550"}} {{attachment:Partial Directed Coherence_AR3.png|Partial Directed Coherence_AR3.png|height="400",width="550"}} |

{{attachment:Directed transfer function_AR3.png|Directed transfer function_AR3.png|width="550",height="400"}} {{attachment:Partial Directed Coherence_AR3.png|Partial Directed Coherence_AR3.png|width="550",height="400"}} |

| Line 68: | Line 61: |

| The coherence is a statistical measure which computes the relation between two signals, like x(t) and y(t), in the frequency domain. The magnitiude-squared coherence is, | The coherence is a statistical measure which computes the relation between two signals, like x(t) and y(t), in the frequency domain. The magnitude-squared coherence is, |

| Line 101: | Line 94: |

| {{attachment:CohProcess_Aug19.PNG||height="400",width="350"}} | {{attachment:CohProcess_Aug19.PNG||width="350",height="400"}} |

| Line 115: | Line 108: |

| {{attachment:CohResults1_Aug19.PNG||height="350",width="670"}} <<BR>><<BR>><<BR>> | '''TODO''': Explain why there are zero-values in the matrix (threshold p<0.05, formulas, references) {{attachment:CohResults1_Aug19.PNG||width="670",height="350"}} <<BR>><<BR>><<BR>> |

| Line 119: | Line 114: |

| {{attachment:StatCoherence_Process_lc.PNG||height="400",width="350"}} <<BR>><<BR>> And finally, "lagged coherence": {{attachment:StatCoherence-Results_lc.PNG||height="300",width="650"}} <<BR>><<BR>> |

{{attachment:StatCoherence_Process_lc.PNG||width="350",height="400"}} <<BR>><<BR>> And finally, "lagged coherence": {{attachment:StatCoherence-Results_lc.PNG||width="650",height="300"}} <<BR>><<BR>> |

| Line 134: | Line 129: |

| {{attachment:StatGranger_Process.PNG||height="400",width="350"}} <<BR>><<BR>> | {{attachment:StatGranger_Process.PNG||width="350",height="400"}} <<BR>><<BR>> |

| Line 150: | Line 145: |

| {{attachment:StatGranger-Results_AR.PNG||height="350",width="350"}} <<BR>><<BR>> Spectral Granger causality {{attachment:StatGrangerSpect_Process.PNG||height="400",width="350"}} <<BR>><<BR>> {{attachment:StatGrangerSpect-Results_AR.PNG||height="350",width="350"}} <<BR>><<BR>> == Coherence and envelope (Hilbert/Morlet) == This process {{attachment:FlowChartHCorr.png||height="170",width="850"}} <<BR>><<BR>> |

By running the process function, the Granger causality can be displayed in a matrix. <<BR>><<BR>> {{attachment:GrangerMatrixRes2.png||width="350",height="350"}} <<BR>><<BR>> <<BR>><<BR>> The upper right element of this matrix shows there is a signal flow from channel 1 to channel 3. However, the Granger function by itself cannot represent the transfer function (frequency spectrum). To do that, we need to run the Spectral Granger causality. {{attachment:GrangerSpecProcess3.png||width="350",height="400"}} <<BR>><<BR>> Here, is that process similar to the previous function with two extra options. These include the frequency resolution and maximum frequency of interest which was discussed previously in the Coherence process. As a result, the power spectrum of the transfer function is depicted: <<BR>><<BR>> {{attachment:SpecResultGranger2.png||width="400",height="350"}} <<BR>><<BR>> <<BR>><<BR>> It shows a clear peak at 25 Hz, as expected. == Coherence and envelope Correlation by Hilbert transform and Morlet wavelets == In chapter 24, the Morlet wavelets and Hilbert transform were fully introduced and examined as tools to decompose signals in the time-frequency domain. This representation can be used for computing the coherence and related measures as well. Besides the lagged and Imaginary Coherence, which were discussed earlier in this tutorial, a measure named "envelope correlation" was found in 2010 '''(ref)'''. This method work based on the pairwise orthogonalization of signals, removing their real part of coherence, and computing the correlation between the orthogonalized parts. The entire process alleviates the effect of volume conduction in MEEG signals. This method has shown to work well on resting-state MEG. In late 2019, we launched our newly designed process called "HCoh". This process and its corresponding functions compute the Coherence, lagged-coherence, and envelope correlation using the Hilbert transform and Morlet wavelets. By splitting the signals and employing the Parallel processing toolbox (if applicable and available), it is capable of analyzing long recordings and a high number of channels in an efficient time. The complete mathematical background about this process is presented in the "advanced" section. The general framework can be simplified as {{attachment:FlowChartHCorr.png||width="850",height="170"}} <<BR>><<BR>> Now, we are ready to start working with this process. |

| Line 165: | Line 174: |

| * Run the process: '''Connectivity > HCorr NxN ''' <<BR>><<BR>> {{attachment:DynHCorr_Process.PNG||height="550",width="400"}} |

* Run the process: '''Connectivity > HCoh NxN ''' <<BR>><<BR>> {{attachment:DynHCorr_Process.PNG||width="400",height="550"}} |

| Line 170: | Line 179: |

| * '''Time-frequency transformation method:''' The method for this transformation (Hilbert transform or Morlet Wavelet) should be selected. Additionally, this analysis needs further inputs, e.g. frequency ranges, number of bins, and Morlet parameters, which can be defined by an external panel as depicted in Figure 4 (By clicking on “Edit”). A complete description regarding time-frequency transformation can be found here. In the context of connectivity study, we must analyze complex output values of these functions, so two other options (power and magnitude) are disabled on the bottom of this panel. | * '''Time-frequency transformation method:''' The method for this transformation (Hilbert transform or Morlet Wavelets) should be selected. Additionally, this analysis needs further inputs, e.g. frequency ranges, number of bins, and Morlet parameters, which can be defined by an external panel as depicted in Figure 4 (By clicking on “Edit”). A complete description regarding time-frequency transformation can be found here. In the context of connectivity study, we must analyze complex output values of these functions, so two other options (power and magnitude) are disabled on the bottom of this panel. |

| Line 173: | Line 182: |

| * '''Parallel processing:''' This feature, which is only applicable for envelope correlation, employs the parallel processing toolbox in Matlab to fasten the computational procedure. As described in the advanced section of this tutorial, envelope correlation utilizes a pairwise orthogonalization approach to attenuate the cross-talk between signals. This process requires heavy computation, especially for a large number of channels, however, using Parallel Processing Toolbox, the software distributes calculations on several threats of CPU. The maximum number of pools varies on each computer and it is dependent on the CPU. | * '''Parallel processing:''' This feature, which is only applicable for envelope correlation, employs the parallel processing toolbox in Matlab to accelerate the computational procedure. As described in the advanced section of this tutorial, envelope correlation utilizes a pairwise orthogonalization approach to attenuate the cross-talk between signals. This process requires heavy computation, especially for a large number of channels, however, using Parallel Processing Toolbox, the software distributes calculations on several CPU threads. The maximum number of pools varies on each computer and it is dependent on the CPU. |

| Line 175: | Line 184: |

== Phase locking value == An alternative class of measures considers only the relative phase through the computation of a phase locking value between the two signals (Tass et al., 1998). Phase locking is a fundamental concept in dynamical systems that has been used in control systems (the phase-locked loop) and in the analysis of nonlinear, chaotic and non-stationary systems. Since the brain is a nonlinear dynamical system, phase locking is an appropriate approach to quantifying interaction. A more pragmatic argument for its use in studies of LFPs (local field potentials), EEG and MEG is that it is robust to fluctuations in amplitude that may contain less information about interactions than does the relative phase (Lachaux et al., 1999; Mormann et al., 2000). The most commonly used phase interaction measure is the Phase Locking Value (PLV), the absolute value of the mean phase difference between the two signals expressed as a complex unit-length vector (Lachaux et al., 1999; Mormann et al., 2000). If the marginal distributions for the two signals are uniform and the signals are independent then the relative phase will also have a uniform distribution and the will be zero. Conversely, if the phases of the two signals are strongly coupled then the PLV will approach unity. For event-related studies, we would expect the marginal to be uniform across trials unless the phase is locked to a stimulus. In that case, we may have nonuniform marginals which could in principle lead to false indications of phase locking. Phase synchronization between two narrow-band signals is frequently characterized by the Phase Locking Value (PLV). Consider a pair of real signals s1(t) and s2(t), that have been band-pass filtered to a frequency range of interest. Analytic signals can be obtained from s1(t) and s2(t) using the Hilbert transform: {{{#!latex \begin{eqnarray*} z_{i}(t)= s_{i}(t) + j HT\left ( s_{i}(t) \right ) \\ \end{eqnarray*} }}} Using analytical signals, the relative phase between z1(t) and z2(t) can be computed as, {{{#!latex \begin{eqnarray*} \Delta \phi (t)= arg\left ( \frac{z_{1}(t)z_{2}^{*}(t)}{\left | z_{1}(t) \right |\left | z_{2}(t) \right |} \right ) \\ \end{eqnarray*} }}} The instantaneous PLV is {{{#!latex \begin{eqnarray*} PLV(t)= \left | E\left [ e^{j\Delta \phi (t)} \right ] \right | \\ \end{eqnarray*} }}} <<BR>> |

|

| Line 183: | Line 220: |

| {{attachment:StatCorrelation_Process.PNG||height="350",width="350"}} | {{attachment:StatCorrelation_Process.PNG||width="350",height="350"}} |

| Line 190: | Line 227: |

| == Phase locking value == <<BR>><<BR>> |

|

| Line 196: | Line 230: |

| {{attachment:TableComparison.PNG||height="400",width="700"}} | {{attachment:TableComparison.PNG||width="700",height="400"}} |

| Line 200: | Line 234: |

| {{attachment:Coh13_AR3.png||height="350",width="600"}} | {{attachment:Coh13_AR3.png||width="600",height="350"}} |

| Line 217: | Line 251: |

| {{attachment:GE_brain.png||height="200",width="390"}} {{attachment:GE_electrodePosition.png||height="200",width="300"}} | {{attachment:GE_brain.png||width="390",height="200"}} {{attachment:GE_electrodePosition.png||width="300",height="200"}} |

| Line 240: | Line 274: |

| {{attachment:lfpTimeLine.png||height="400",width="680"}} | {{attachment:lfpTimeLine.png||width="680",height="400"}} |

| Line 264: | Line 298: |

| {{attachment:DeleteFiles.png||height="250",width="380"}} | {{attachment:DeleteFiles.png||width="380",height="250"}} |

| Line 273: | Line 307: |

| {{attachment:PLV_EarlyAnswerWithERP.png||height="650",width="380"}} | {{attachment:PLV_EarlyAnswerWithERP.png||width="380",height="650"}} |

| Line 283: | Line 317: |

| As explained above, we will focuse on the early response in which we expect high connectivity measures on the striate and prestriate areas. For the late response, we expect high measures on/between the occipital and motor cortex du to the eventual hand movements.. | As explained above, we will focus on the early response in which we expect high connectivity measures on the striate and prestriate areas. For the late response, we expect high measures on/between the occipital and motor cortex du to the eventual hand movements.. |

| Line 297: | Line 331: |

| {{attachment:plv_early_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:plv_early_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:plv_early_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:plv_early_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 303: | Line 337: |

| {{attachment:plv_early_go_band1_image_ncm.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:plv_early_nogo_band1_image_ncm.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} As we saw before, the highest value are between the electrodes 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 which are in the occipital cortex. |

{{attachment:plv_early_go_band1_image_ncm.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:plv_early_nogo_band1_image_ncm.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} As we saw before, the highest values are between the electrodes 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 which are in the occipital cortex. |

| Line 309: | Line 343: |

| From the Process2 bar, we can compute the difference between the images in order to highlight the main difference between the two condition. To do that, you jus drag the associated connectivity file for the condition one to the Files A and the condition two to the files B, then click on run, select Difference, then one of the proposed options, in this tutorial we selected the 'Normalized: A-B/A+B'. {{attachment:plv_early_go_band1_image-plv_early_nogo_band1_image_ncm.PNG||height="450",width="690"}} | From the Process2 bar, we can compute the difference between the images in order to highlight the main difference between the two condition. To do that, you jus drag the associated connectivity file for the condition one to the Files A and the condition two to the files B, then click on run, select Difference, then one of the proposed options, in this tutorial we selected the 'Normalized: A-B/A+B'. {{attachment:plv_early_go_band1_image-plv_early_nogo_band1_image_ncm.PNG||width="690",height="450"}} |

| Line 317: | Line 351: |

| {{attachment:plv_late_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:plv_late_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:plv_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:plv_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 329: | Line 363: |

| {{attachment:plv_late_go_band1_image-plv_late_nogo_band1_image_ncm.PNG||height="450",width="690"}} | {{attachment:plv_late_go_band1_image-plv_late_nogo_band1_image_ncm.PNG||width="690",height="450"}} |

| Line 343: | Line 377: |

| {{attachment:PLVnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:PLVnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:PLVnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:PLVnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 349: | Line 383: |

| {{attachment:PLVnoERP_late_go_band1_bis.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:PLVnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:PLVnoERP_late_go_band1_bis.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:PLVnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 360: | Line 394: |

| {{attachment:COH_early_go_band2.PNG||height="260",width="345"}} {{attachment:COH_early_nogo_band2.PNG||height="260",width="345"}} | {{attachment:COH_early_go_band2.PNG||width="345",height="260"}} {{attachment:COH_early_nogo_band2.PNG||width="345",height="260"}} |

| Line 368: | Line 402: |

| {{attachment:COH_late_go_band2.PNG||height="260",width="345"}} {{attachment:COH_late_nogo_band2.PNG||height="260",width="345"}} | {{attachment:COH_late_go_band2.PNG||width="345",height="260"}} {{attachment:COH_late_nogo_band2.PNG||width="345",height="260"}} |

| Line 378: | Line 412: |

| {{attachment:COHnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||font-size="10pt",height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:COHnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||font-size="10pt",height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:COHnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:COHnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 384: | Line 418: |

| {{attachment:COHnoERP_late_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:COHnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:COHnoERP_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:COHnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 393: | Line 427: |

| {{attachment:CORR_late_go_band1.PNG||font-size="10pt",height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:CORR_late_nogo_band1.PNG||font-size="10pt",height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:CORR_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:CORR_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 397: | Line 431: |

| {{attachment:CORRnoERP_late_go_band1.PNG||font-size="10pt",height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:CORRnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||font-size="10pt",height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:CORRnoERP_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:CORRnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 404: | Line 438: |

| {{attachment:SGC_early_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGC_early_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} In this example, we see that reciprocal causal influences existe between the electrodes of the striate and the prestriate. |

{{attachment:SGC_early_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGC_early_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} In this example, we see that reciprocal causal influences existe between the electrodes of the striate (1,2,3) and the prestriate(4,5,6). We can also see that the the channel 1 initiates the exchange, and physiologically, the striate cortex precedes prestriate cortex in the anatomical organisation of the visual system. |

| Line 412: | Line 446: |

| {{attachment:SGC_late_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGC_late_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} '''Early response:''' without ERP ---- . distance filtering : 0mm, threshold 2.5, band1 12.5 {{attachment:SGC_early_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGC_early_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} late response: with erp |

{{attachment:SGC_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGC_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} '''__Early response__ t ϵ [100-250 ms] :''' Parameters : 0mm, threshold 2.5, band1 12.5, without ERP {{attachment:SGC_early_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGC_early_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} '''__Late response__ t ϵ [250-400 ms] :''' Parameters : 0mm, threshold 0.315, band1 12.5 {{attachment:SGC_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGC_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} Early response: without ERP ---- . distance filtering : 0mm, threshold ~0.5, band1 12.5 {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} ---- '''Late response: '''without ERP ---- |

| Line 425: | Line 473: |

| {{attachment:SGC_late_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGC_late_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:SGC_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGC_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 429: | Line 477: |

| ---- | |

| Line 432: | Line 479: |

| {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} ---- '''Late response: '''without ERP ---- . distance filtering: 0mm, threshold 0.315, band1 12.5 {{attachment:SGC_late_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGC_late_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} Early response: without ERP . distance filtering : 0mm, threshold ~0.5, band1 12.5 {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} |

{{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 453: | Line 486: |

| {{attachment:SGCnoERP_late_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:SGCnoERP_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 459: | Line 492: |

| /!\ '''Edit conflict - other version:''' ---- |

|

| Line 463: | Line 494: |

| {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_early_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 469: | Line 500: |

| {{attachment:SGCnoERP_late_go_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||height="240",width="345"}} | {{attachment:SGCnoERP_late_go_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} {{attachment:SGCnoERP_late_nogo_band1.PNG||width="345",height="240"}} |

| Line 474: | Line 505: |

| == TODO : Connectivity measure on MEG data == | == TODO : Connectivity measure on real data : MEG/EEG data == |

| Line 505: | Line 536: |

| {{attachment:connectivitySourceSpace.png||height="400",width="500"}} | {{attachment:connectivitySourceSpace.png||width="500",height="400"}} |

| Line 511: | Line 542: |

| In this tutorial, we will use the scouts " Destrieux atlas'''" (following figure)''' {{attachment:destrieuxScouts.png||height="400",width="500"}} | In this tutorial, we will use the scouts " Destrieux atlas'''" (following figure)''' {{attachment:destrieuxScouts.png||width="500",height="400"}} |

| Line 517: | Line 548: |

| {{attachment:processConnectivityScouts.png||height="400",width="300"}} | {{attachment:processConnectivityScouts.png||width="300",height="400"}} |

| Line 523: | Line 554: |

| {{attachment:connectivityScoutDistrieux.png||height="400",width="500"}} | {{attachment:connectivityScoutDistrieux.png||width="500",height="400"}} |

| Line 569: | Line 600: |

| {{attachment:MatrixDeviantCorDestrieuxTime1.PNG||height="400",width="500"}} {{attachment:GraphDeviantCorDestrieuxTime1.PNG||height="400",width="600"}} | {{attachment:MatrixDeviantCorDestrieuxTime1.PNG||width="500",height="400"}} {{attachment:GraphDeviantCorDestrieuxTime1.PNG||width="600",height="400"}} |

| Line 581: | Line 612: |

| {{attachment:MatrixDeviantCorDestrieuxTime1.PNG||height="400",width="500"}} {{attachment:GraphDeviantCorDestrieuxTime1.PNG||height="400",width="600"}} | {{attachment:MatrixDeviantCorDestrieuxTime1.PNG||width="500",height="400"}} {{attachment:GraphDeviantCorDestrieuxTime1.PNG||width="600",height="400"}} |

| Line 587: | Line 618: |

| {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} {{attachment:GraphDeviantPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} | {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} {{attachment:GraphDeviantPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} |

| Line 591: | Line 622: |

| {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} } {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} | {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} } {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} |

| Line 597: | Line 628: |

| {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} {{attachment:GraphDeviantPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} | {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} {{attachment:GraphDeviantPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} |

| Line 602: | Line 633: |

| {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} } {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} | {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} } {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvDestrieuxBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} |

| Line 608: | Line 639: |

| {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_All.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} | {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_All.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_all.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} |

| Line 613: | Line 644: |

| {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} | {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} |

| Line 625: | Line 656: |

| {{attachment:GraphStandardPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||height="300",width="345"}} '''<<TAG(Advanced)>> ''' ''TODO : discuss '' |

{{attachment:GraphStandardPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} {{attachment:GraphDevianPlvMEGBandbetaHzTime3_Max.PNG||width="345",height="300"}} ''TODO : discuss'' |

| Line 643: | Line 672: |

| '''<<TAG(Advanced)>>''' |

|

| Line 644: | Line 675: |

| ''' {{attachment:GC_Math_Time2.PNG||height="450",width="700"}} ''' | ''' {{attachment:GC_Math_Time2.PNG||width="700",height="450"}} ''' |

| Line 659: | Line 690: |

== Sections to add == * Discuss option concatenate vs. average for the estimation of coherence on single trials: https://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/difference-between-averaging-coherence-and-concatenate/22726/4 * Discuss pValues computed for the various methods == On the hard drive == '''TODO''': Document data storage. |

|

| Line 663: | Line 701: |

| * Phase transfer entropy''': Lobier M, Siebenhühner F, Palva S, Palva JM [[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053811913009191|Phase transfer entropy: A novel phase-based measure for directed connectivity in networks coupled by oscillatory interactions]], NeuroImage 2014, 85:853-872 ''' | * Lagged-Coherence: Pascual-Marqui RD. [[https://arxiv.org/pdf/0706.1776|Coherence and phase synchronization: generalization to pairs of multivariate time series, and removal of zero-lag contributions]], arXiv preprint arXiv:0706.1776. 2007 Jun 12. * Phase transfer entropy: Lobier M, Siebenhühner F, Palva S, Palva JM [[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053811913009191|Phase transfer entropy: A novel phase-based measure for directed connectivity in networks coupled by oscillatory interactions]], NeuroImage 2014, 85:853-872 * Barzegaran E, Knyazeva MG. [[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181105|Functional connectivity analysis in EEG source space: The choice of method]] Ward LM, editor. PLOS ONE. 2017 Jul 20;12(7):e0181105. |

| Line 666: | Line 708: |

| * '''Connectivity matrix storage:[[http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/showthread.php?1796-How-the-Corr-matix-is-saved|http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/showthread.php?1796]] ''' * '''Comparing coherence values: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/showthread.php?1556 ''' * '''Reading NxN PLV matrix: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/pte-how-is-the-connectivity-matrix-stored/4618/2 ''' * '''Scout function and connectivity: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/showthread.php?2843 ''' * '''Unconstrained sources and connectivity: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/problem-with-surfaces-vs-volumes/3261 ''' * '''Digonal values: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/choosing-scout-function-before-or-after/2454/2 ''' * '''Connectivity pipeline: https://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/help-for-connectivity-pipeline/12558/4 ''' * '''Ongoing developments: https://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/connectivity-tutorial-and-methods-development-on-bst/12223/3 ''' * '''Granger causality: https://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/is-granger-causality-analysis-a-linear-operation/12506/12 ''' '''<<HTML(<!-- END-PAGE -->)>> ''' '''<<EmbedContent("http://neuroimage.usc.edu/bst/get_prevnext.php?prev=Tutorials/GroupAnalysis&next=Tutorials/Scripting")>> ''' '''<<EmbedContent(http://neuroimage.usc.edu/bst/get_feedback.php?Tutorials/Connectivity)>> ''' |

* Connectivity matrix storage:[[http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/showthread.php?1796-How-the-Corr-matix-is-saved|http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/showthread.php?1796]] * Comparing coherence values: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/showthread.php?1556 * Reading NxN PLV matrix: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/pte-how-is-the-connectivity-matrix-stored/4618/2 * Export multiple PLV matrices: https://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/export-multiple-plv-matrices/2014/4 * Scout function and connectivity: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/showthread.php?2843 * Unconstrained sources and connectivity: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/problem-with-surfaces-vs-volumes/3261 * Digonal values: http://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/choosing-scout-function-before-or-after/2454/2 * Connectivity pipeline: https://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/help-for-connectivity-pipeline/12558/4 * Ongoing developments: https://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/connectivity-tutorial-and-methods-development-on-bst/12223/3 * Granger causality: https://neuroimage.usc.edu/forums/t/is-granger-causality-analysis-a-linear-operation/12506/12 <<HTML(<!-- END-PAGE -->)>> <<EmbedContent("http://neuroimage.usc.edu/bst/get_prevnext.php?prev=Tutorials/GroupAnalysis&next=Tutorials/Scripting")>> <<EmbedContent(http://neuroimage.usc.edu/bst/get_feedback.php?Tutorials/Connectivity)>> |

Tutorial 28: Connectivity

[TUTORIAL UNDER DEVELOPMENT: NOT READY FOR PUBLIC USE]

Authors: Hossein Shahabi, Mansoureh Fahimi, Francois Tadel, Esther Florin, Sergul Aydore, Syed Ashrafulla, Takfarinas Medani, Elizabeth Bock, Sylvain Baillet

Cognitive and perceptual functions are the result of coordinated activity of the functionally specialized neural modules distributed in the brain. Brain connectivity investigates how these neural modules (or nodes) interact as a network, with the goal of having a better understanding of how the brain processes information under certain functions. Depending on which connectivity characteristic is studied, a distinction is made between structural (fiber pathways), functional (non-directed statistical dependency) and effective (causal interaction) connectivity between regions. Effective connectivity is often referred as directed functional connnectivity. In these tutorial we will see how to perform functional an effective connectivity analyses in Brainstorm, firstly with simulated data and later with real data.

Contents

- General considerations in connectivity analysis

- Simulated data (AR model)

- Coherence (FFT-based)

- Granger Causality

- Coherence and envelope Correlation by Hilbert transform and Morlet wavelets

- Phase locking value

- Correlation

- Method selection and comparison

- Connectivity measures on real data : LFP data

- TODO : Connectivity measure on real data : MEG/EEG data

- TODO : Connectivity measure on real data : MEG/EEG data

- Granger Causality - Mathematical Background

- Sections to add

- On the hard drive

- Additional documentation

General considerations in connectivity analysis

Sensors or sources: Connectivity analysis can be performed on sensor data (EEG/MEG signals) or on reconstructed sources (voxels or scouts).

Recording condition: While connectivity analysis can be performed on resting-state (spontaneous) and event-related (trials) recordings, the appropriate connectivity method depends on the recording condition.

Point-based connectivity vs. full network: Connectivity can be computed between one node (aka seed) and the rest of the nodes in the network (1 x N approach), or between all the possible node pairs in the network (N x N approach). While the later calculates the detailed connectivity graph, the 1 x N approach is faster to compute and it is more useful when you are interested in the connectivity of a ROI with the other regions of the brain.

Temporal resolution: Connectivity networks can be computed in two ways; static and dynamic. Time-varying networks can present the dynamics of brain networks. In contrast, the static graphs illustrate a general perspective of brain connectivity which is helpful in specific conditions. Users need to decide which type of network is more informative for their study.

Time-frequency transformation: Many connectivity methods rely on the time-frequency representation of the data. These approaches include short time Fourier transform, Hilbert transform, and Morlet wavelet.

Simulated data (AR model)

In order to compare different connectivity measures, we use simulated data with known ground truth. Consider three channels constructed using the following autoregressive (AR) process.

where aij and bi are coefficients of 4th order all-pole filters. These coefficients were calculated in a way that the first channel has a dominant peak in the Beta band (25 Hz), the second channel shows the highest power in the Alpha band (10 Hz), and a similar level of energy in both bands in the third signal. bi describe the transfer function from channel 1 to channel 3 and values are selected where it should have a peak in the Beta band.

Using these coefficients, we simulate signals (Fs = 100). The connectivity measures will be tested by this dataset, which is available here.

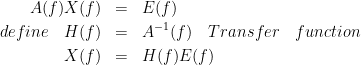

One can take the Fourier transform from the AR equations and rearrange them in a matrix form.

By calculating the H(f), we will have:

In this figure, the diagonal elements show the auto transfer function, which in our specific case is the spectrum of the signals. The off-diagonal terms represent the interactions between different signals. Here, we see the transfer function from channel 1 to channel 3.

Besides the original transfer function, we can compute the directed transfer function (DTF) and partial directed coherence (PDC). Details about those measures can be found in ref.

Coherence (FFT-based)

The coherence is a statistical measure which computes the relation between two signals, like x(t) and y(t), in the frequency domain. The magnitude-squared coherence is,

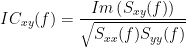

The coherence function uses the Fourier transform to compute the spectral densities. Two related measures, which alleviate the problem of volume conduction, are imaginary and lagged coherence. More information regarding these measures can be found here. The formulas for computing the two values are as follows:

Imaginary Coherence:

Lagged Coherence:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

LC_{xy}(f) = \frac{Im \left (S_{xy}(f) \right )}{\sqrt{ S_{xx}(f)S_{yy}(f) - \left [ Re\left ( S_{xy}(f) \right ) \right ]^{2} }} \\

\end{eqnarray*} \begin{eqnarray*}

LC_{xy}(f) = \frac{Im \left (S_{xy}(f) \right )}{\sqrt{ S_{xx}(f)S_{yy}(f) - \left [ Re\left ( S_{xy}(f) \right ) \right ]^{2} }} \\

\end{eqnarray*}](/brainstorm/Tutorials/Connectivity?action=AttachFile&do=get&target=latex_800c7c6d6923f7c1a323462a6746f1ec8dbdca42_p1.png)

where Im() and Re() describe the imaginary and real parts of the spectral densities.

To calculate coherence values in Brainstorm:

- Put the Simulated data in the Process1 tab.

- Click on [Run] to open the Pipeline editor.

Run the process: Connectivity > Coherence NxN

- Set the options as follows:

Time window: Select the entire signal.

Removing evoked response: Check this box to remove the averaged evoked response from the individual trials.

Measure: You can select either the "Magnitude-Squared" coherence or the "Imaginary" coherence. we first select the former one.

Maximum frequency resolution: This value characterizes the distance between frequency bins. Smaller values give higher resolutions but probably noisier.

Highest frequency of interest: It specifies the highest frequency which should be analyzed. Here, we selected Fs/2 = 125 Hz to have the coherence in all frequencies.

Output configuration: Select one file per input file.

In general, after running the connectivity processes, you can find a multi-dimensional matrix of connectivity in the database. In order to represent this matrix, there are several options.

Right-click on the file and select Power spectrum and Display as image. These two figures are plotted here. The left figure shows the Coherence values in all analyzed frequencies. Another figure displays the Transfer matrix between channels for the selected frequency bin.

TODO: Explain why there are zero-values in the matrix (threshold p<0.05, formulas, references)

Similarly, we can run this process and select "imaginary coherence", which gives us the following representation,

And finally, "lagged coherence": ![]()

We see the last two measures are similar but have different values in several frequencies. However, both imaginary and lagged coherence are more accurate than coherence.

Granger Causality

Granger Causality (GC) is a method of functional connectivity, adapted by Clive Granger in the 1960s, but later refined by John Geweke in the form that is used today. Granger Causality is originally formulated in economics but has caught the attention of the neuroscience community in recent years. Before this, neuroscience traditionally relied on stimulation or lesioning a part of the nervous system to study its effect on another part. However, Granger Causality made it possible to estimate the statistical influence without requiring direct intervention (ref: wiener-granger causality a well-established methodology).

Granger Causality is a measure of linear dependence, which tests whether the variance of error for a linear autoregressive model estimation of a signal (A) can be reduced when adding a linear model estimation of a second signal (B). If this is true, signal B has a Granger Causal effect on the first signal A, i.e., independent information of the past of B improves the prediction of A above and beyond the information contained in the past of A alone. The term independent is emphasized because it creates some interesting properties for GC, such as that it is invariant under rescaling of A and B, as well as the addition of a multiple of A to B. The measure of Granger Causality is nonnegative, and zero when there is no Granger causality(Geweke, 1982).

The main advantage of Granger Causality is that it is an asymmetrical measure, in that it can dissociate between A->B versus B->A. It is important to note however that though the directionality of Granger Causality is a step closer towards measuring effective connectivity compared to symmetrical measures, it should still not be confused with “true causality”. Effective connectivity estimates the effective mechanism generating the observed data (model-based approach), whereas GC is a measure of causal effect based on prediction, i.e., how well the model is improved when taking variables into account that are interacting (data-driven approach) (Barrett and Barnett, 2013). The difference with causality is best illustrated when there are more variables interacting in a system than those considered in the model. For example, if a variable C is causing both A and B, but with a smaller delay for B than for A, then a GC measure between A and B would show a non-zero GC for B->A, even though B is not truly causing A (Bressler and Seth, 2011).

The complete formulation of this method is discussed in the advanced section. Here, we apply the Granger causality and its spectral version on the simulated data.

- Put the Simulated data in the Process1 tab.

- Click on [Run] to open the Pipeline editor.

Run the process: Connectivity > Bivariate Granger causality NxN

Input options:

Time window: specifies the time window you want to use for your model.

Remove evoked response from each trial: this option refers to subtracting the average of phase-locked activity (ERP) from each individual trial. Presently some studies measure interdependency of ongoing brain activity by removing the average event-related potential from each trial. It is also recommended by some as it meets the zero-mean stationarity requirement (improves stationarity of the system). However, the problem with this approach is that it does not account for trial-to-trial variability (For a discussion see (Wang et al., 2008) todo-> link to paper).

Estimator options:

Model order: Selection of model order is a critical issue and is typically evaluated from criteria derived from information theory. Several criteria have been proposed, of which the most used are Akaike’s information criterion, the Bayesian-Schwartz’s criterion, and the Hannan-Quinn criterion (Koichi and Antonio, 2014 link). Model fitting quality crucially depends on the proper model order selection. Too low orders may lack the necessary details, while too big orders tend to create spurious values of connectivity. Note that in our simulated example even though the simulation was created with an underlying model of 4, a Granger model order of 6 was selected with decent resulting connectivity.

Output options:

Save individual results (one file per input file): option to save GC estimates on several files separately.

Concatenate input files before processing (one file): option to save GC estimates on several files as one concatenated matrix.

By running the process function, the Granger causality can be displayed in a matrix.

The upper right element of this matrix shows there is a signal flow from channel 1 to channel 3. However, the Granger function by itself cannot represent the transfer function (frequency spectrum).

To do that, we need to run the Spectral Granger causality. ![]()

Here, is that process similar to the previous function with two extra options. These include the frequency resolution and maximum frequency of interest which was discussed previously in the Coherence process. As a result, the power spectrum of the transfer function is depicted:

It shows a clear peak at 25 Hz, as expected.

Coherence and envelope Correlation by Hilbert transform and Morlet wavelets

In chapter 24, the Morlet wavelets and Hilbert transform were fully introduced and examined as tools to decompose signals in the time-frequency domain. This representation can be used for computing the coherence and related measures as well.

Besides the lagged and Imaginary Coherence, which were discussed earlier in this tutorial, a measure named "envelope correlation" was found in 2010 (ref). This method work based on the pairwise orthogonalization of signals, removing their real part of coherence, and computing the correlation between the orthogonalized parts. The entire process alleviates the effect of volume conduction in MEEG signals. This method has shown to work well on resting-state MEG.

In late 2019, we launched our newly designed process called "HCoh". This process and its corresponding functions compute the Coherence, lagged-coherence, and envelope correlation using the Hilbert transform and Morlet wavelets. By splitting the signals and employing the Parallel processing toolbox (if applicable and available), it is capable of analyzing long recordings and a high number of channels in an efficient time.

The complete mathematical background about this process is presented in the "advanced" section. The general framework can be simplified as

Now, we are ready to start working with this process.

- Put the Simulated data in the Process1 tab.

- Click on [Run] to open the Pipeline editor.

Run the process: Connectivity > HCoh NxN

Input Options: The time range of the input signal can be specified here. Also, bad channels and the evoked response of trials can be discarded, if appropriate.

Time-frequency transformation method: The method for this transformation (Hilbert transform or Morlet Wavelets) should be selected. Additionally, this analysis needs further inputs, e.g. frequency ranges, number of bins, and Morlet parameters, which can be defined by an external panel as depicted in Figure 4 (By clicking on “Edit”). A complete description regarding time-frequency transformation can be found here. In the context of connectivity study, we must analyze complex output values of these functions, so two other options (power and magnitude) are disabled on the bottom of this panel.

Signal splitting: This process has the capability of splitting the input data into several blocks for performing time-frequency transformation, and then merging them to build a single file. This feature helps to save a huge amount of memory and, at the same time, avoid breaking a long-time recording to short-time signals, which makes inconsistency in dynamic network representation of spontaneous data. The maximum number of blocks which can be specified is 20.

Connectivity measure: Here, three major and widely used coherence based measures of brain connectivity can be computed. Next, desired parameters for windowing, i.e. window length and overlap, should be determined. Please note that these values are usually defined based on the nature of data, the purpose of the study, and the selected connectivity measure.

Parallel processing: This feature, which is only applicable for envelope correlation, employs the parallel processing toolbox in Matlab to accelerate the computational procedure. As described in the advanced section of this tutorial, envelope correlation utilizes a pairwise orthogonalization approach to attenuate the cross-talk between signals. This process requires heavy computation, especially for a large number of channels, however, using Parallel Processing Toolbox, the software distributes calculations on several CPU threads. The maximum number of pools varies on each computer and it is dependent on the CPU.

Output configuration: Generally, the above calculation results in a 4-D matrix, where dimensions represent channels (1st and 2nd dimensions), time points (3rd dimension), and frequency (4th dimension). In the case that we analyze event-related data, we have also several files (trials). However, due to poor signal to noise ratio of a single trial, an individual realization of connectivity matrices for each of them is not in our interests. Consequently, we need to average connectivity matrices among all trials of a specific event. The second option of this part performs this averaging.

Phase locking value

An alternative class of measures considers only the relative phase through the computation of a phase locking value between the two signals (Tass et al., 1998). Phase locking is a fundamental concept in dynamical systems that has been used in control systems (the phase-locked loop) and in the analysis of nonlinear, chaotic and non-stationary systems. Since the brain is a nonlinear dynamical system, phase locking is an appropriate approach to quantifying interaction. A more pragmatic argument for its use in studies of LFPs (local field potentials), EEG and MEG is that it is robust to fluctuations in amplitude that may contain less information about interactions than does the relative phase (Lachaux et al., 1999; Mormann et al., 2000).

The most commonly used phase interaction measure is the Phase Locking Value (PLV), the absolute value of the mean phase difference between the two signals expressed as a complex unit-length vector (Lachaux et al., 1999; Mormann et al., 2000). If the marginal distributions for the two signals are uniform and the signals are independent then the relative phase will also have a uniform distribution and the will be zero. Conversely, if the phases of the two signals are strongly coupled then the PLV will approach unity. For event-related studies, we would expect the marginal to be uniform across trials unless the phase is locked to a stimulus. In that case, we may have nonuniform marginals which could in principle lead to false indications of phase locking.

Phase synchronization between two narrow-band signals is frequently characterized by the Phase Locking Value (PLV). Consider a pair of real signals s1(t) and s2(t), that have been band-pass filtered to a frequency range of interest. Analytic signals can be obtained from s1(t) and s2(t) using the Hilbert transform:

Using analytical signals, the relative phase between z1(t) and z2(t) can be computed as,

The instantaneous PLV is

![\begin{eqnarray*}

PLV(t)= \left | E\left [ e^{j\Delta \phi (t)} \right ] \right | \\

\end{eqnarray*} \begin{eqnarray*}

PLV(t)= \left | E\left [ e^{j\Delta \phi (t)} \right ] \right | \\

\end{eqnarray*}](/brainstorm/Tutorials/Connectivity?action=AttachFile&do=get&target=latex_10f68832e53b9fba0f2c3add3817f05fdd0229f1_p1.png)

Correlation

The correlation is the basic approach to show the dependence or association among two random variables or MEG/EEG signals. While this method has been widely used in electrophysiology, it should not be considered as the best technique for finding the connectivity matrices. The correlation by its nature fails to alleviate the problem of volume conduction and cannot explain the association in different frequency bands. However, it still can provide valuable information in case we deal with a few narrow-banded signals.

- Put the Simulated data in the Process1 tab.

- Click on [Run] to open the Pipeline editor.

Run the process: Connectivity > Correlation NxN

- Set the options as follows:

Time window: Select the entire signal.

Estimator options: leave the box unchecked so the means will be subtracted before computing the correlation.

Output configuration: Select one file per input.

Method selection and comparison

We can have a comparison between different connectivity functions. The following table briefly does this job.

Comparing different approaches with the ground truth we find out that the HCorr function works slightly better than other coherence functions.

Connectivity measures on real data : LFP data

In this section we will show how to use the Brainstorm connectivity tools on real data.

LFP data recorded on monkey

Experimental Setup and data recording:

For this part we will use the Local Field Potential (LFP) monkey data described in Bresslers et al (1993), these data are widely used over the last past years in many studies.

The original data could be found in this link, more information on the data organization is explained here and also here.

These recordings were made using 15 surface-to-depth bipolar electrodes, separated by 2.5mm, implanted in the cerebral hemisphere contralateral to the monkey's prefered hand.For our analysis in this tutorial, we have selected the monkey named GE.

The data are recorded from 6 main areas of the right cortex (Straite, Prestriate, Parietal, Somato, Motor, and frontal cortex). The approximative locations of the 15 electrodes are shown in this figure. The are digitazed at 200sample per second (200Hz).

On the left, a scheme of the monkey brain area, on the right, the locations of 15 electrode pairs in the right hemisphere (reproduced from Aydore et al (2013) and Bresslers et al (1993)).

In these experiments, the monkey was trained to depress a lever and wait for a visual stimulus that informs the monkey to either let go the lever (release/GO) or keep the lever down (not release/NOGO). The visual stimulus is presented with four dots arranged as a left (or right) slanted line or diamand on a display screen. (The dots form either a shape of a diagonal line or a shape of a diamond.)

For our analysis in this tutorial, we select a dataset with a diagonal line as the 'NOGO' stimulus and the diamond as the 'GO'.

For more details about the experiment please refer to Bresslers et al (1993) and to this page.

Importing and analyzing data within brainstorm:

For our case, we imported and adapted the data to the brainstorm format, you can download a sample of the data here. (todo >this sample contains only 50 epochs per condition, the full data should uploaded asap)

Voltage is in uV and was recorded at 200Hz sampling rate. After pooling and ordering the dataset together, we randomly select 480 trials for each condition (GO and NOGO) with only one conctingency for condition (only one kind of stimulation for each condition).

Timeline explanation

Defining the lever initial descent to be at time t = 0ms. Each trial lasts 600ms, the stimulus was given 100ms after the lever was depressed, and last for 100ms. On GO trials, a water reward was provided 500 ms after stimulus onset only if the hand was lifted within the 500ms. On the NOGO trials, the lever was depressed for 500ms.

In the following figure, we show the time line of the averaged response for the 480 epochs for the GO condition. The blue line is at t = 0ms begening of the recording, the green line is the stimulus onset at t = 100ms, the orange line is the mean time of the response onset in the case of the GO condition (release the lever), the red line is the time cursor, set at t = 250ms, time that we choose to separate between early response and late response in this tutorial.

In this analysis, we will focus mainly on two windows. The early response for t ϵ[100, 250 ms] in which we expect a visual activation on the occipital area (striate and prestriate areas, group of electrodes 1 to 6). We will also show some analysis on the late response, for t ϵ [250, 450 ms] in which we expect an activation/connectivity between the striate and motor cortex in the GO condition and no or less activation for the NOGO condition.

Process of computation:

For most of the connectivity measures, we will use the following steps :

First we compute the the connectivity value between one pair of electrode (or scouts) for each trial (time serie), in this case we have 480 trials for each condition, therefore we will compute 480 values for each pair of electrods. After that we will average the connectivity over all the trails and we will get the average value for the pair of electrodes. As explained in the previous sections, Brainstorm offers two options, the NxN (matrix) or 1xN (vector) measures, whre N is the number of channel.

- Step 1 : Drag and drop all the trials for both condition in Process1 tab.

- Step 2 : Click on [Run] to open the Pipeline editor. Select the desired connectivity measure, choose the desired parameters (see bellow) and click on Run the computation.

- After running the connectivity processes, you can find a multi-dimensional matrix of connectivity in the database. This matrix (or vector) is computed for each trial. But in this case s=we need to average all these data.

- Step 3 : Average the connectivity measure for all trial bellonging the same condition.

On the Process1, select the option 'time freq' process, and click on Run. Select the process "Average > Average files". Select the options: By trial group (folder), Arithmetic average, Keep all the event markers, then lunch to computation.

- An average of the connectivity measure is computed and appeares in the Brainstorm database window.

Remove intermediate data :

To free space in your hard disc and in order to be able to compute other connectivity meaure, you can/should remove the previous individual connectivity for each trial. To do so, keep the 'time freq' in process1, click Run and choose : File>Delete File>Delete selected Files and then click on run. This process will delet the individual data for each trial.

Phase Locking Value (PLV)

We select the two groupes of files in the the process 1 (drag and drop), then hit Run, select Connectivity then Phase Locking Value NxN. Choose time window between 100 to 250ms (for early analysis and later 250 to 450 ms for the late response).

For Hilbert transform, we select bands from 12 to 60 Hz as shown in the fugure. The PLV is more accurate on short frequency band and to pretend for significant value we recommend to use time windows with more than 100 samples (it's not the cqse in this data).

For the remaining, keep the other options as they are, select the Magnitude and choose the option 'Save individual results (one file per input file)' and finaly click on Run.

This could take some times according to your computer and the size of your data.

Now, in order to have one measure for each condition, we need to average all the connectivity measure across trials. We do this from the Brainstorm Process1 window, select 'Process time-freq' (the third icone). Then click on run and select : Average->Average Files, select the option : By trial group (folder average) with the function Arithmetic average. This will compute the average connectivity PLV matrix for the Go and NoGo stimulus.

In order to represent this matrix, there are several options.

Right click on the connectivity file and select the first option > Display as graph [NxN]. We display both figures for the GO (left figure) and NOGO (right figure) conditions.

As explained above, we will focus on the early response in which we expect high connectivity measures on the striate and prestriate areas. For the late response, we expect high measures on/between the occipital and motor cortex du to the eventual hand movements..

Early response t ϵ [100-250 ms]:

The first option to display the results is: select the connectivity file in the database, right-click and then choose the first option "Display as a graph" From the brainstorm control panel "Display", we can tune the value of the frequency band from the cursor. Same options are available for the connectivity threshold and for the distance filtring.

Intensity threshold: You can play with the cursor of threshold in order to show more or less connectivity between the nodes.

Distance filtering: set a limit physical distance between two nodes (electrodes in this example).

Frequency band selection: Some of the method compute the connectivity within the frequency band, as the PLV, in this case, you have to select the band with a cursor

For these data we don't have the exact location of the electrode on the cortex, we build an approximation of the location, therefore we will set the distance filtering to zero in this case.

For the following figure, we choose 0mm, band1, threshold 0.844.

As we expected, the results show high connectivity value (PLV) between the striate and prestriate area. The strength of the measures is almost the same for both conditions, however, we observe some difference on the electrodes between the Line and the Diamond, this is probably due to the difference on the shape (patern) of the visual stimuli.

We will also display the connectivity matrix as an image, either by selecting the measure and press 'Enter' or Right-click on the connectivity file and select the first option > Display as an image [NxN]

As we saw before, the highest values are between the electrodes 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 which are in the occipital cortex.

To highlight the difference between the two conditions, we can use the Process2 and compute the difference between the two images. (Further methods for statistics are under development)

From the Process2 bar, we can compute the difference between the images in order to highlight the main difference between the two condition. To do that, you jus drag the associated connectivity file for the condition one to the Files A and the condition two to the files B, then click on run, select Difference, then one of the proposed options, in this tutorial we selected the 'Normalized: A-B/A+B'. ![]()

The resulted image shows the highest difference in the connectivity is between the electrodes (2,6) and (3,6), this is exactely the difference that we observed in the previous graphes, which is mainly the difference between the two conditions. There is also diference in the paires (1,14), (8,14) and (11,14), which involves the visuql, the motor and the frontal cortexes, probably due to the preparation to the decision making, and prepare to activate or inhibite the action of the hand.

Late response t ϵ [250-450 ms] :

distance filtering : 0mm, band1, threshold 0.644

In this late response, also as we expected, we see higher value in the GO condition then the NOGO condition. Also we observe a connexion between the striate to motot cortex, this connection is related to the mouvmenet of the hand to release the lever.

These results show also the connection between the striat/prestiriate to the frontal regions since this later is involved in the selection of actions based on perceptual cues and reward values as shown in this paper.

These connectivity results are highly correlated to the ones observed within the previous publications Aydore et al. (2013) and Bresslers et al (1993). We should also notice that is in this process, the difference in the result is related to the implementation methods, the selected time windows and the sample data size and choice (here we picked randomly 480 samples from each condition).

As in previous, we will visualize the results as an image for the difference between the two conditions.

Of course, ultimately statistical analysis of these maps is required to make scientific inferences from your data.

From this matrix, we can check pixels by pixels the different values and combinations of electrodes, we notice a slight difference between the electrodes (1,4), (2,4), (1,8), (2,9), (2,10), (4,8), (7,8) but also it shows the highest value between (3,9) and (9,14) wich is related to the connection between the visual cortex to the motor cortex and to the frontal cortex.

Remove the ERP from the signal:

As explained in the previous sections, some connectivity measures can be estimated without the the ERP, this option brings the signals to a slightly more stationary state [Wang and al]

If we choose the option that remove the ERP from each trial before computing the connectivity, we end up with these results (todo : remove the erp is not available on bst for plv for now) :

Early response t ϵ [100-250 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, band1, threshold 0.75

Late response t ϵ [250-450 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, band1, threshold 0.666

We observe coherent results with this option. For the early response, a new connextion in the cortex motor between the node (10,11) is highlighted. For the late response, more connextion value are visible in the cas of GO condition.

Coherence (COH)

We use the same data as previous, and we will compute the coherence. We will try to show similar results as shown in the Bresslers et al (1993) in which high value of coherence are observed between the striate and motor cortex areas for the GO condition within the freauency band 12-25 Hz.

Early response t ϵ [100-250 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, band2, threshold 0.5, with the ERP

For both conditions, we observe similar value.

Late response t ϵ [250-450 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, band2, threshold 0.35, with the ERP

As expected, in this case, high value of the coherence are observed for the GO condition (>0,6) wherease for the NOGO condition this value is less than 0,4. We noticed also connection between the visual striate and prestriate to the motor cortex in the GO condition.

Results without the ERP :

Early respinse t ϵ [100-250 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, band1, threshold 0.35,

Late response t ϵ [250-450 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, band1, threshold 0.66

Correlation (COR)

We use the same data as previous, and we will compute the correlation. As explained before, the correlation is the basic and simple method to observe interaction between region.

Late response t ϵ [250-450 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, threshold 0.7, with the ERP

Parameters : 0mm, threshold 0.63, without the ERP

Spectral Granger Causality (SGC)

Early response t ϵ [100-250 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, threshold 2.5, band1 12.5, with the ERP

In this example, we see that reciprocal causal influences existe between the electrodes of the striate (1,2,3) and the prestriate(4,5,6). We can also see that the the channel 1 initiates the exchange, and physiologically, the striate cortex precedes prestriate cortex in the anatomical organisation of the visual system.

Late response t ϵ [250-450 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, threshold 0.315, band1 12.5, with ERP

Early response t ϵ [100-250 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, threshold 2.5, band1 12.5, without ERP

Late response t ϵ [250-400 ms] :

Parameters : 0mm, threshold 0.315, band1 12.5

Early response: without ERP

- distance filtering : 0mm, threshold ~0.5, band1 12.5

Late response: without ERP

- distance filtering: 0mm, threshold 0.315, band1 12.5

Early response: without ERP

- distance filtering : 0mm, threshold ~0.5, band1 12.5

Late response: without ERP

- distance filtering : 0mm, threshold ~0.27, band1 12.5

Phase Transfer Entropy (PTE)

early with erp 0,1, b1. 0mm ...not relevant > recheck

TODO : Connectivity measure on real data : MEG/EEG data

Late response: without ERP

- distance filtering : 0mm, threshold ~0.27, band1 12.5

Phase Transfer Entropy (PTE)

early with erp 0,1, b1. 0mm ...not relevant > recheck

TODO : Connectivity measure on real data : MEG/EEG data

For all the brain imaging experiments, it is highly recommended to have a clear hypothesis to test before starting the analysis of the recordings. With this auditory oddball experiment, we would like to explore the temporal dynamics of the auditory network, the deviant detection, and the motor response. According to the literature, we expect to observe at least the following effects:

Bilateral response in the primary auditory cortex (P50, N100), in both experimental conditions (standard and deviant beeps).

Bilateral activity in the inferior frontal gyrus and the auditory cortex corresponding to the detection of an abnormality (latency: 150-250ms) for the deviant beeps only.

Decision making and motor preparation, for the deviant beeps only (after 300ms).

The first response peak (91ms), the sources with high amplitudes are located around the primary auditory cortex, bilaterally, which is what we are expecting for auditory stimulation.

- For this experiment we will focus on the beta high and gamma frequency, as shown here

https://brainworksneurotherapy.com/what-are-brainwaves, "Beta is a ‘fast’ activity, present when we are alert, attentive, engaged in problem-solving, judgment, decision making, or focused mental activity."

- 1 dataset:

S01_AEF_20131218_02_600Hz.ds: Run #2, 360s, 200 standard + 40 deviants

For this data we select three main time windows to compute the connectivity:

time 1 : 0-150 ms : we expect the bilateral response in the primary auditory cortex (P50, N100), in both experimental conditions (standard and deviant beeps).

time 2 : 100-300 ms: Bilateral activity in the inferior frontal gyrus and the auditory cortex corresponding to the detection of an abnormality (latency: 150-250ms) for the deviant beeps only.

time 3 : 300-550 ms : Frontal regions activation related to the decision making and motorpreparation, for the deviant beeps only (after 300ms).

The computation are done here only for the second recording.

Sources level

Connectivity is computed at the source points (dipole) or at a defined brain region also called scouts. The signal used art this level is obtained from the inverse problem process, in which each source-level node (dipole) is assigned with an activation value at each time point.

Therefore, we can compute the connectivity matrix between all pairs of the node. This process is possible only of the inverse problem is computed (ref to tuto here).

To run this in brainstorm, you need to drag and drop the source files within the process1 tab, select the option 'source process' click on the Run button, then you can select the connectivity measure that you want to perform.

As in the previous section, we can compute the source connectivity matrix for each trail, then average overall trial. However, this process is time and memory consuming. For each trial, a matrix of 15002x15002 elements is computed and saved in the hard disc (~0.9 Go per trial). In the case of the unconstrained source, the size is 45006x45006.

This is obviously a very large number and it does not really make sense. Therefore, the strategy is to reduce the dimensionality of the source space and adopt a parcellation scheme, in other terms we will use the scouts. Instead, to compute the connectivity value values between two dipoles, we will use a set of dipoles pairs that belong to a given area in the cortex.

Although the choice of the optimal parcellation scheme for the source space is not easy. The optimal choice is to choose a parcellation based on anatomy, for example the Brodmann parcellation here. In brainstorm these atlases are imported in Brainstorm as scouts (cortical regions of interest), and saved directly in the surface files as explained in this tutorial here.

In this tutorial, we will use the scouts " Destrieux atlas" (following figure) ![]()

To select this atlas, from the connectivity menu, you have to check the box 'use scouts', select the scout function 'mean' and apply the function 'Before', save individual results.

In this tutorial, we select the correlation as example, the same process is expected for the other methods.

For more detail for these options please refer to this thread

The following matrix is the solution that we obtain with these scouts with the size of 148x148 for this atlas (~400 Ko)

For this data we select three main time windows to compute the connectivity:

time 1 : 0-150 ms : we expect the bilateral response in the primary auditory cortex (P50, N100), in both experimental conditions (standard and deviant beeps).

time 2 : 100-300 ms : Bilateral activity in the inferior frontal gyrus and the auditory cortex corresponding to the detection of an abnormality (latency: 150-250ms) for the deviant beeps only.

time 3 : 300-550 ms : Frontal regions activation related to the decision making and motor preparation, for the deviant beeps only (after 300ms).

The computation are done here only for the second recording.

Coherence

Correlation

For this data we select three main time windows to compute the connectivity:

time 1 : 0-150 ms : we expect the bilateral response in the primary auditory cortex (P50, N100), in both experimental conditions (standard and deviant beeps).

time 2 : 100-300 ms : Bilateral activity in the inferior frontal gyrus and the auditory cortex corresponding to the detection of an abnormality (latency: 150-250ms) for the deviant beeps only.

time 3 : 300-550 ms : Frontal regions activation related to the decision making and motor preparation, for the deviant beeps only (after 300ms).